Dedicated to Polish Arts and Culture Since 1946

Welcome - Witamy!

|

|

|

Polish Arts Club of Trenton, New Jersey

Dedicated to Polish Arts and Culture Since 1946 Welcome - Witamy! |

|

A Two-Country Freedom Fighter A book review from the Wall St. Journal June 20, 2009 |

By ARAM BAKSHIAN JR.

When the great African-American educator and human-rights pioneer Booker T. Washington visited Krakow, Poland, in 1910, he made a special point of paying tribute to a dead white male with the nigh-unpronounceable name of Tadeusz Andrzej Bonawentura Kosciuszko. “I knew from my school history what Kosciuszko had done for America in its early struggle for independence,” Washington would later write. “I did not know, however, until my attention was called to it in Krakow, what Kosciuszko had done for the freedom and education of my own people. . . . When I visited the tomb of Kosciuszko, I placed a rose on it in the name of my race.” In his views on race, as in so many other matters, Tadeusz (Thaddeus in English) Kosciuszko (1746-1811) was a man ahead of his time. A freedom fighter on two continents, he did not hesitate to denounce the evils of slavery while playing a crucial role as chief engineer in America’s fledgling Continental Army. In his native Poland, he appealed to the patriotism of the privileged classes as he championed full civil rights for the disenfranchised majority of Poland’s peasants, Jews and city-dwelling commoners. But he also upheld the rule of law and opposed mob violence. He was, in the words of French historian Jules Michelet, “the last knight, but the first citizen in Slavic lands with a modern understanding of brotherhood and equality.” Despite his heroic efforts, Kosciuszko’s fatherland had to wait a century after his death before regaining independence from Russia. The world would have to wait even longer for an accessible, soundly researched, English-language biography. With “The Peasant Prince,” Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Alex Storozynski has filled the void. |

|

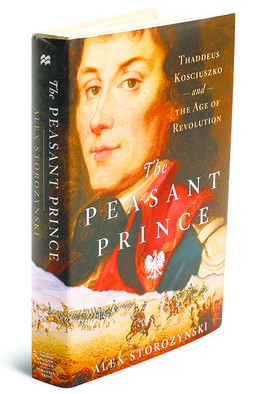

Book Details The Peasant Prince By Alex Storozynski Thomas Dunne, 370 pages, $29.95 |

And what a tale he has to tell. A melodramatic, foiled elopement deprived the young Kosciuszko of the love of his life and led him to cross the Atlantic and sign up with George Washington’s ragtag rebel army. The Polish émigré engineered the network of fortifications around West Point that Benedict Arnold unsuccessfully tried to betray to the British and that helped keep the main British army bottled up in New York City. Kosciuszko also played a key role in the wilderness campaigns that ended in the crucial American victory at Saratoga. And he made a triumphal return to his native Poland in time to lead a doomed but heroic national struggle against Russia and overwhelming odds.

All this and a supporting cast that amounts to a Who’s Who of 18th-century American and European history. In America, those who knew Kosciuszko included Benjamin Franklin (who helped recruit him); George Washington (who had trouble getting Kosciuszko’s name right but hailed him as a military “engineer of eminence”); Thomas Jefferson (who called him “as pure a son of liberty as I have ever known”); and Thomas Paine (who, like Kosciuszko, was granted honorary French citizenship by the revolutionary regime but spoke out against its brutal excesses). In Europe, Kosciuszko’s acquaintances included Napoleon Bonaparte (who tried—and failed—to use him as a pawn in European power politics) and Catherine the Great (who, after ruthlessly suppressing the Polish insurrection, kept Kosciuszko a political prisoner in Russia until her death in 1796). |

Mr. Storozynski painstakingly provides context and ample documentation for this remarkable story, although he occasionally missteps: Prussia was not yet a “Kingdom” in 1683, muskets are not rifles, military turrets are not “minarets,” and the guillotine, far from being “new” at the execution of Louis XVI in 1793, had been used for a least a year to separate common criminals from their heads.

But the virtues of “The Peasant Prince” far outweigh its few sins against fact. Mr. Storozynski does a particularly good job of explaining the topsy-turvy nature of 18th- century Poland, a decayed feudal “Royal Republic” headed by an elected king—the charming, well-intentioned but terminally spineless Stanislaw Augustus Poniatowski. He was a bon vivant, patron of the arts and involuntarily retired lover of Catherine the Great—but dominated by a venal, arrogant handful of wealthy aristocratic families. Between them and the Polish masses stood the lesser gentry—the traditional backbone of Poland’s army, the bulk of the nation’s severely limited “electorate” and the class from which Kosciuszko himself was sprung. Even as Poland’s stronger neighbors began nibbling at her borders, a national awakening in the spirit of the 18th-century Enlightenment resulted in a burst of intellectual life and educational reform in Poland during Kosciuszko’s childhood. One result was that, as the bright younger son of a minor landowner, he was chosen to attend the Royal Knight’s School, the newly established military academy in Warsaw where he received a first-class education, enhanced by his studying art and engineering in Paris. Kosciuszko’s later combat experience in America—and his social observations there— helped him to create the first truly national Polish army, incorporating volunteers from the burgher class, thousands of serfs and peasants armed only with scythes, and even a Jewish cavalry regiment that may have been the first purely Jewish military formation since biblical times. Under his inspiring leadership, these disparate elements combined with patriotic members of the clergy and aristocracy to form the first mass nationalist movement in central and eastern Europe. That it was eventually crushed by the first—but not the last—cynical Berlin-Moscow alliance was no wonder. That Kosciuszko was able to score several impressive victories before being crushed by overwhelming force was miraculous. Once released from czarist imprisonment, the battle-scarred Polish paladin led a mostly anticlimactic life in exile. He refused to be taken in by Napoleon, who, Kosciuszko rightly predicted, “will not resurrect Poland—he thinks only of himself. He detests every great nation and especially the spirit of independence. He’s a despot, and his only aim is personal ambition. He will not create anything durable.” But Kosciuszkoalso failed to persuade the allied powers at the Congress of Vienna to honor Poland’s right to national existence. His last years were spent in Swiss exile, a modest, kindly old soldier. Kosciuszko’s will included a provision that some of his fortune should be used to buy the freedom of American slaves and to pay for their education. The scheme, audiacious for its time, seemed to unnerve Thomas Jefferson, the executor, who feared that the fragile new country was unprepared for such a step toward universal liberty. Jefferson recused himself as executor and, alas, Kosciuszko’s estate was never used as he had hoped. Were he with us today, Kosciuszko would probably be more amused than annoyed by the fact that many Americans know his name only as a brand of mustard (with out the “z”). Or they might be familiar with Kosciuszko as the designation of a bridge linking Brooklyn and Queens in New York. The bridge, like the man, has served for the benefit of countless millions. —Mr. Bakshian writes frequently on politics, history and food. |

|

|